Kaj: Gideon, thanks for taking time to be interviewed by Projekt Fredrika – about the Jews in Finland and their relationship to the Swedish language!

Let me start by telling the audience that this interview wasn’t originally meant to happen in English. We initially exchanged some emails in Swedish, our common native language. Then you concluded by sending me a note in German, because we both happen to live in Germany today – you in Berlin, me in Munich. And Corona has us both currently spending a lot of time the relative safety of our native Finland (for which you used the patriotic Swedish term “fosterland”). Am I correct so far?

Gideon: I deliberately used the term “dear fatherland” (dyra fosterland) playing with the double meaning of the word “dyra”, which means both dear and expensive. And we both know, that living in Finland is much more expensive than in Germany.

Kaj: Let me continue by telling the readers that I am changing to English here for a somewhat odd reason: “Show, don’t tell”. I have launched Projekt Fredrika to make the Swedish dimension of Finland more known. We can tell people that Swedish is an official language in Finland until we’re blue in our face, that there are 300.000 Finland Swedes, most of whom didn’t learn Finnish until at school, and quite a few of whom didn’t use Finnish extensively until an adult age – if at all. But still, even educated foreigners often don’t know we exist. Instead, they ask us “are you Finns or Swedes?”. Have you had such experiences?

Gideon: Of course! But my situation is more complicated than yours. The overall Jewish attitude towards Finland Swedish, linguistically East-Swedish, is a non-trivial topic. And I suppose that is part of what makes you curious enough to ask for this interview, right?

Gideon Bolotowsky at the Helsinki Book Fair in 2011. Gideon was the chairman of the Jewish Community of Helsinki from 1989 to 2007. Photo: Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0

Kaj: Indeed it is! Thanks for bringing us back to the main theme of Jews in Finland, and their language over time. The purpose of Projekt Fredrika’s “Show, don’t tell” policy is that we want people to stumble upon our existence, when they least expect it. We want to illustrate that Finland is not just Finnish, through random historical facts. And the relationship of Jews in Finland with the Swedish language is one such fact. According to your Wikipedia article in Finnish, you were the chairman of the Jewish congregation of Helsinki 1989-2007. Educate me, what does that role mean in practice? As in Finland there is no equivalent of the German Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland, that made you somewhat of a spokesperson for all Jews in Finland, towards the press, I assume?

Gideon: Let me correct you here; Finnish Jews do have a similar central body as the Zentralrat is for German Jews. Ours is called the Central Council of Jewish Communities in Finland. As Helsinki was and is the dominant community, the chairperson of the Central Council is usually the chairperson of the Helsinki Community. Consequently I did in my time have the mandate to speak on behalf of all Finnish Jews.

Kaj: So my topic here is language. What language(s) did and do the Jews of Finland speak?

Gideon: Historically, the Jews in Finland picked their language usage because of natural, logical reasons.

1. The first Jews in Finland were so called cantonists, meaning: Russian conscripts signing on to work within the Russian Imperial Army, from the age of 12 years. They came to Finland starting in the 1830s. They knew Russian, but they spoke Yiddish as their native language.

2. Swedish was the administrative language of Finland, nearly without exception, throughout the 19th century and well into the 20th century.

3. The roots of Yiddish are medieval German, making Swedish, which also belongs to the Germanic family of languages, much easier to learn than Finnish.

Kaj: So did the Jews then assimilate in Finland by changing their Yiddish to Swedish?

Gideon: Yes. With increasing emancipation, Swedish was more and more becoming the home language in the families of Helsingfors (Finnish: Helsinki) and Åbo (Finnish: Turku). In the third major Jewish congregation, Wiborg (Finnish: Viipuri), Jews started to speak Finnish earlier than elsewhere.

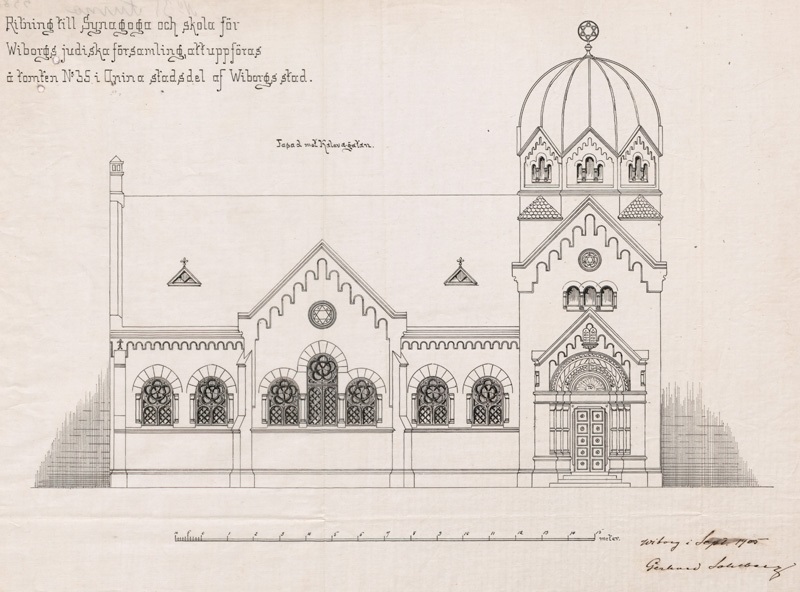

Kaj: A side note: I looked at the drawing of the Wiborg synagogue, built in 1909-10 and bombed out by the Soviets on the starting day of the Winter War 30.11.1939, and it is in Swedish only. Any comment on that?

Gideon: As I told you, well into the 20th century the administration, the academia and the intellectuals were mostly Swedish speaking. The native language of the architect of the synagogue, Bruno Sohlberg, was definitely Swedish. Besides, linguistically Wiborg, which was seized by Stalin post WWII, was the most international city in Finland. The majority spoke Finnish, but the city housed also important minorities, who spoke Swedish, German, Russian and Yiddish. All the minutes and protocols of the meetings within the Jewish Community of Wiborg were written in Yiddish.

”Ritning till Synagoga och skola för Wiborgs judiska församling ”by architect Bruno Gerhard Sohlberg in 1905. From Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Kaj: By the way, the title of that Wikipedia article is “Vyborg Synagogue”. You write “Wiborg”. Particularly given the above history, I find the usage of transcribed Russian somewhat strange, if not an outright offensive choice of language. As someone connected to people with roots in that congregation, what is your view?

Gideon: Allow me to be a little legalistic here: One of the most important documents in Jewish Law is the Ketubah (marriage certificate), which is only valid if the place and time are clearly defined. And the place in every Ketubah, which has been written in Vyborg is unequivocally Wiborg just like Helsingfors is written as the place of marriage in every Ketubah written in the city of Helsinki. The Jews used the Swedish names of the cities they dwelled in. Nothing offensive about that – on the contrary quite cultural.

Kaj: But back the main topic: When the Jews got civil rights in Finland, shortly after Finland’s independence 1917, what language was spoken at school? Was there a separate Jewish school?

Gideon: Indeed, a Jewish school (“Judiska skolan”) was established in 1918. The language of tuition was Swedish. In the wake of the language feuds in Finland in the 1930s, the language of tuition changed to Finnish.

Kaj: Did you go to this school?

Gideon: My parents attended the Swedish Jewish School in Helsinki. I myself attended the Finnish Jewish School in Helsinki. Same school, different language of tuition.

Kaj: What language did you speak at home with your parents?

Gideon: We spoke exclusively Swedish at home. My parents spoke Yiddish with each other, when they didn’t want us children to understand.

Kaj: How good is your Yiddish?

Gideon: Pretty good. As a German and Hebrew speaker with rudimentary knowledge of Russian I pretty much get along with my Lithuanian Yiddish, which by the way is the literary Yiddish like Mandarin for the Chinese.

Kaj: When do you use your Yiddish?

Gideon: Basically just to show off with those few others who also speak Yiddish.

Kaj: And out of further curiosity, the same question about your Hebrew. How good is it? And how much do you use it?

Gideon: My Hebrew is pretty good and I use it much more frequently than Yiddish with my Israeli friends. After all, my grandfather was the 1st Hebrew teacher in the Helsinki Jewish School.

Kaj: In your daily life, you use all of Swedish, Finnish, German, and English, right?

Gideon: Yes; and Hebrew and Yiddish.

Kaj: Interesting. But back to the topic of Swedish. Are you Swedish or Finnish? For context: French has one top-level word, “Finlandais”, for concepts and people being associated with Finland, which comes in two language flavours, “Finnois” and “Suédois”. Sadly, English uses “Finnish” for both the country (of which I am a highly patriotic citizen), and the language (which I seldom use; I’m better at German and English, than at Finnish). So, which one are you? Finnois or Suédois?

Gideon: Neither. I do not define myself through language. I am, first and foremost, a Jew. Specifically, I am a Jew from Finland. My native language is Swedish. I have great sympathy for the Finland Swedes as a minority, but I am not one myself. Neither am I a Finn, in the language sense. But yes, I am “finlandais”, and as you pointed out somewhere else, I call Finland my “fosterland”, which indeed is a patriotic word.

Kaj: This brings me to another question. So you identify as “finlandais”, but neither “suédois” nor “finnois” – obviously “juif”. That’s more complicated than what can simply be depicted on Wikipedia. And it goes to the minutiae of definitions. There is a category “Finland Swedes”. For all practical purposes, that means “Citizen of Finland [or its legal predecessors before 1917] speaking Swedish as a native language”. You don’t self-identify as “Finland Swede”, but you are well within the boundaries of that definition. Do you mind being listed into such a category?

Gideon: On the contrary. In every census and in every questionnaire for official statistical purposes I insist on being listed as a ‘Finland Swede’. For two reasons: Firstly out of solidarity with the Swedish speaking minority I as a representative of two minorities – the Swedish speakers and the Jews - find it natural to support a minority. Particularly, when I according to the Finnish constitution belong to this minority of people in Finland, whose mother tongue is Swedish. In my case there’s an added twist: Finland being officially bi-lingual, there are certain public officials, who have to prove sufficient proficiency (the big language test) in the other native language ( Swedish or Finnish), which is not the applicant’s mother tongue. I have attended the Jewish School, where the language of tuition is Finnish and received my matriculation from a Finnish speaking Gymnasium. I wrote my thesis at the Technical University of Helsinki in Finnish. Consequently, if I were to apply for a job as a civil servant with this requirement of lingual proficiency, I would in such a case by definition be categorised as a Finnish speaking Finn, and would be compelled to take the big language test in my own mother tongue – Swedish. Quite weird actually, but bureaucracy often is. Secondly: Official questionnaires in Finland have no third option for ethnicity or religion. I can only choose between being a Finnish speaking Finn or a “Finland Swede”. Complicated. Life is! But it’s a much richer life.

Kaj: Wow! Complicated identity, indeed. Part of your multi-faceted identity is difficult to understand for someone like me. Sure, I too have several identities – “European” for one – but language is a very strong component of who I am. If there is anything that I am “first and foremost”, then it would be “Finland Swede”. Is your reasoning, “First and foremost a Jew”, typical for other Jews, too?

Gideon: I think it is. For me, language is an instrument of communication, not so much a part of my self definition. The situation is/was similar elsewhere in Europe. Take Prague before WW II. Among the inhabitants there were 40.000 Germans, and 40.000 German speaking Jews, such as Franz Kafka. Most of the Prag Jews had German (and not Yiddish) as their native language. But at the same time, they were not “Germans”, neither in their own eyes, nor in the eyes of the Germans or the Czech. They were European Jews, of the old K.u.K. (Austro-Hungarian Empire).

Kaj: How did this manifest itself after WW II in Finland?

Gideon: The families who primarily wanted to give their children a Jewish identity put them into the Jewish school (80-90 %). The families who felt closer ties to the Finland Swedish aspects of their identity, than their Jewish identity, put their children into Swedish schools (10-20 %). But that’s a severely shortened story. I’m sure you could make an academic dissertation out of all this!

Kaj: I won’t do that dissertation, even if I find it interesting. I am trying to cram the insights from talking to you into a concise statement that would work for Wikipedia, eg. in the article on Maccabi World Union. What do you say about this attempt:

The oldest Jewish sports club in the world that has an uninterrupted history is Makkabi Helsinki, founded 1906 under the Swedish name IK Stjärnan. A Swedish name was used as a majority of the Jews in Finland at that time primarily used Swedish as their native language, integrating themselves into the Finland Swedish minority.

Gideon: Ich winsch dir Mazel und Glick (Yiddish for I wish you good fortune and luck). And I might add: _The founding of Jewish Sports Clubs throughout Europe in the early 20th century coincided with and was inspired by the rise of Zionism. The names of the clubs, like Bar-Kochba Berlin, Hakoach Wien, Stjärrnan in Helsinki all emulated sources of ancient Jewish pride and strength. IK is Swedish for SC (Sports Club) and Stjärnan (star in English) was of course the Star of David, the logo of the sports club. Later as the name of the club was changed to Makkabi (in Turku/Åbo to Makkabe) the Star of David -logo remained. _

Kaj: Anything else you wish to add? What should I have asked, but didn’t understand to ask?

Gideon: Europe is a patchwork of different peoples and nations, often overlapping. It reminds me of the joke, where the Master of Ceremonies to the Throne of Belgium had difficulties to balance the seating around the table between the Flemish and the French. After some wriggling, the chairman of Belgian Jews discreetly asked: “And where, may I ask, do you intend to seat us Belgians?” I am first and foremost a European Jew, who has had the good fortune of being born and raised in Finland in a Swedish speaking family. I’m a 4th generation “Finlandais”, with even deeper roots in the old Pale and East Prussia. From my perspective: a vibrant and strong European Union would be the best that could befall all Europeans.

Kaj: Thank you! Tack! Or, as you’ve taught me: Jiskoiach – a greissn Dank!

For more reading, see

History of the Jews in Finland, on English Wikipedia

Judar i Finland, on Swedish Wikipedia

Projekt Fredrika improves the coverage of Swedish Finland and Swedish in Finland on Wikipedia, in Swedish and other languages. Read more about us (Project page, Projektsidan, Projektisivut, Projektseite, Page du projet, страница проекта) and follow us on Twitter, Facebook or Instagram.

Projekt Fredrika förbättrar täckningen av det svenska i Finland på Wikipedia, främst på svenska men också på andra språk. Läs om oss på Wikipedia (Projektsidan, Project page, Projektisivut, Projektseite, Page du projet, страница проекта, eller följ oss på Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, eller Youtube.